20 mars 2014

Le quiz du Printemps

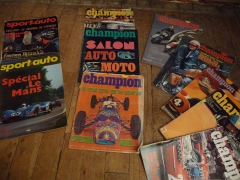

Pour gagner un lot de Sport-Auto & Champion 60' (*) plus ou moins complets, il suffit de répondre le premier et de façon exacte à toutes les questions...

Chaque question bien répondue donne 9, 6, 4, 3, 2 et 1 points aux six premiers dans l'ordre.

(*) Détails à venir.

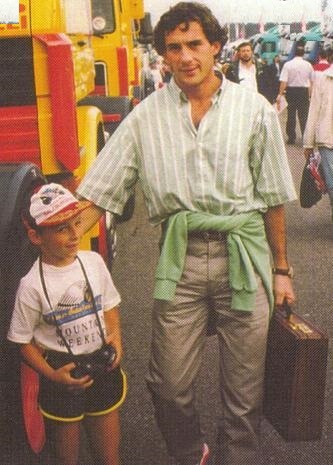

Q1: Qui, quand, où, quelle voiture ?

Q2: Qui, quand (année), quelle voiture ?

Q3: Qui, quand, où, quelle voiture ?

R: Fangio à Indy en 1958 - pas sur la voiture où il était engagée - la Dayton Steel Foundry Special - mais sur la Lew Welch's Kurtis Kraft Novi 3.0 L8C Automotive Air Conditioning Special

Q4: Qui ?

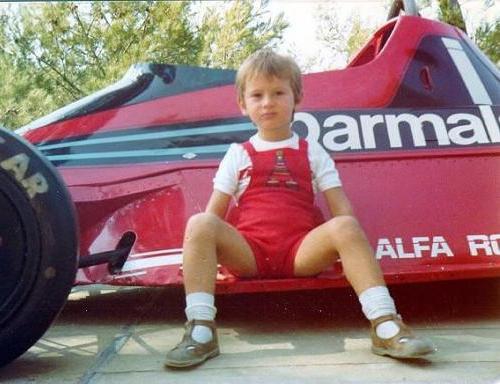

Q5: Quand, quelle voiture ?

R: 1972, Brabham BT39 Weslake V12, boite Hewland FG400. Basé sur un chassis de BT38. Uniquement en tests, moteur pas assez puissant.

Q6: Qui, quand, où, quelle voiture ?

Q7: Qui, quand, où, quelle voiture ?

Q8: Qui, quand ?

Q9 Bonus: Il s'agit de John Miles à la Race of Champions Brands-Hatch 1971

Photo 9 ©G.Swan

Autres photos ©DR

22:01 Publié dans a.senna | Tags : ayrton senna | Lien permanent | Commentaires (17) | ![]() Facebook | |

Facebook | |

12 février 2014

Rétromobile : La confession d’une enfant du XXe siècle

Je m'appelle Ferrari 330 P4 #0858 (1), même si certains s'obstinent à me nommer 350 P4.

Rétromobile a été l'occasion de faire mon grand retour sur la scène parisienne.

S’il est vrai que sur le plan carrière, ma longévité n'est rien face à celle de la Ford GT40 yankee, sans même parler de la Porsche 917 teutonne, à l'applaudimètre j’ai pu constater que je reste une star incontestée.

RMs : Racontez-nous, #0848...

En inspirant profondément, celle-ci plonge dans son propre passé, si loin et si près à la fois :

#0858 : Ça c’est passé il y a 47 ans...

Craignant que #0858 se perde en préliminaires, RMs l’interrompt brusquement :

RMs : On sait ! Essayez juste de vous rappeler quelque chose, n’importe quoi !

Bien décidée de rapporter les faits à sa manière, elle toise Francis du regard avant de le remettre à sa place :

#0858 : Voulez-vous entendre l’histoire ou non, monsieur Memorychaispasquoi ?

Mal à l’aise de se faire gronder comme un enfant devant ses amis et conscient d’avoir sous-estimé la vieille gloire, Francis lui sourit timidement en guise d’excuse. #0858 reprend :

#0858 : Ça c’est passé il y a 47 ans, et je sens encore l’odeur de la peinture fraîche ! Le V12 n’avait presque pas tourné, personne n’avait encore couru à son volant. La Ferrari P4 était surnommée le "prototype de rêves", et il l’était... il l’était vraiment... !

Dans sa mémoire apparait l’autodrome de Monza, en cette fin avril 1967, pendant les essais. Tout à coup le feulement d’un V12 4L troue le silence, des sourires illuminent instantanément le visage des tifosis venus en nombre, enfin la #4 s’engage sur la piste, au volant l’ « ingeniere » Mike Parkes … le pilote-ingénieur de la Scuderia.

#0858 : Je débute sur mes terres à Monza, grée en berlinette #4, avec comme résultat une 2e place derrière l’autre P4.

RMs : Brillants débuts, cela rappelle un peu le triomphe de Daytona en tout début de saison, parlez-en à Bruno ...

#0858 : Une semaine après direction le toboggan des Ardennes, le grand circuit, le vrai, c'est le jour où le mirage devient réalité (2).

RMs : 5e place quand même (#9), toujours avec l’équipage Parkes /Scarfiotti.

#0858 : Ludovico Scarfiotti était le neveu du Signore Agnelli, président de la Fiat.

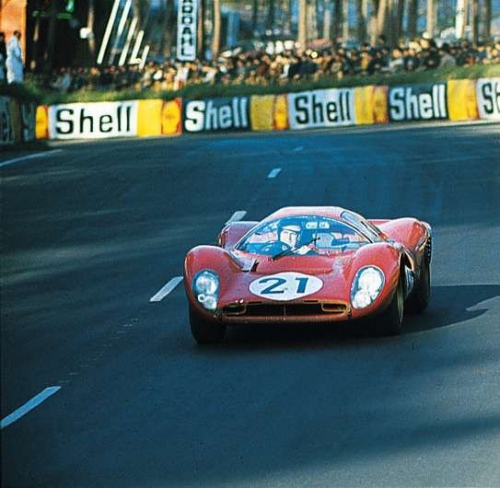

RMs : En juin c'est la course du siècle, les 24H du Mans 1967, la revanche attendue, David contre Goliath...

#0858 : Las, bluffée par les performances un peu ternes de la nouvelle Ford MkIV aux essais d'avril, la Scuderia joue la prudence en limitant la puissance de nos V12. Notre directeur sportif était Franco Lini.

RMs : J'avais passé le week-end à l'écoute de mon transistor sur "Europe 1" ou "France Inter". Quelle déception quand la #21 est rentrée aux stands le dimanche matin lors d’un arrêt non prévu pour changer les plaquettes de frein: 8 mn de perdues, cette fois c'était fini. (3)

#0858 : Mais il faut bien avouer que revenir sur la MK IV de tête avait nécessité beaucoup de la part de Parkes et Scarfiotti. L’italien n'en pouvait plus d'ailleurs, il était dans un état de fatigue... Et ce n’est pas Chris Amon qui a pu sauver la mise ! Avec sa chance habituelle, il n’a pas dépassé la 8e heure.

RMs : Tsss ! Magnifique seconde place quand même, avec en bonus la 3e place de la P4 belge #24.

#0858 : J’ai alors changé une première fois de look. On était en plein « Swinging London », la mode « mini » battait son plein, les mannequins étaient filiformes, on a décidé d’enlever le haut. Je deviens alors barquette et perds ainsi une quarantaine de kilos. Comme équipage on m’affecte deux sujets du Commonwealth, l’anglais Jonathan Williams et l’australien Paul Hawkins, surnommé « Swimming Kangaroo » depuis son plongeon dans le port de Monaco.

RMs : Il s’agissait quand même de rapporter de Brands-Hatch le titre de Champion du Monde,… une solide 6e place récompensera l’équipage britannique, #8.

#0858 : Ferrari avec ses P4 est sacré Champion du Monde des marques 1967. C’est alors que la CSI sort une vraie bombe de son tiroir : limitation à 3L de la cylindrée des Sport-Prototypes à partir de 1968, idée complètement « révolutionnaire » ! Nous voilà, mes camarades et moi, condamnées à une retraite anticipée.

RMs : Le Commendatore eut du mal à digérer l’affront… Finies les Ferrari P4, exclues les Ford 7L, adieu les Chaparral, du Messmer avant l’heure...

#0858 : Je fus alors vendue à l’américain Bill Harrah, de Reno (!) USA, en vue de disputer les épreuves CanAm. Changement de look à nouveau, j’adopte une tenue de spyder très estivale, perds encore des kilos au profit d’un surcroit de puissance, je deviens alors officiellement une 350 P4 Canam.

RMs : Une carrosserie extrêmement séduisante, des résultats un peu moins. Jonathan Williams #27. (4)

#0858 : Changement de continent un an plus tard, je dispute l’épreuve de Surfers Paradies avec l’équipage Chris Amon/David MacKay (#4). Pour 1968 direction l’Afrique du Sud où je pars disputer les Springbok Series aux mains de Paul Hawkins, UK - Team Gunston.

RMs : Les acteurs appellent cela des rôles de complément…

#0858 : Mais l’Europe me manque, et les victoires aussi. C’est triomphalement que je reviens à Magny Cours en mai 1969, pilotée par le grand Mike Hailwood (#85). Le second round à Dijon fut moins glorieux…

RMs : Et puis une robe orange pour une Ferrari…

#0858 : Je termine en 1969 mes folles années de course par une nouvelle Springbok Series drivée par mon nouveau propriétaire Alistair Walker associé pour l’occasion à Robin Widdows (#6).

RMs : Et ensuite ?

#0858 : Il se fait tard. Je vous laisse consulter mes états de service. Très heureuse d’avoir fait votre rencontre.

RMs : Vous êtes toujours aussi séduisante.

#0858 : Et puis je suis bien ici, à Rétromobile. Mon transporteur historique prend soin de moi, et non loin se trouve ma petite cousine la Dino. Elle me ressemble, non ?

RMs (en aparté): les vieilles gloires ne meurent jamais. (5)

Librement adapté du scénario de ‘Titanic’ de James Cameron.

Francis Rainaut

(1) 330 est la cylindrée unitaire, tu multiplies par le nombre de cylindres et tu as la cylindrée totale 3960 cc (Gérard Crozier)

(2) Victoire de Jacky Ickx/Dick Thompson sur Mirage-Ford

(3) Extrait des mémoires de Bruno

(4) J'ai construit il y a quelques années un proto slot-racing avec carrosserie de P4 Canam surbaissée

(5) Même en forçant un peu sur le silicone au niveau des rétros

Illustrations :

- Photos 1, 2, 10, 11 et 12 ©FrancisRainaut

- Photo 6 ©DavidSmall

- Photo 15 ©Champion n°31

- Autres Photos ©DR

Chassis #0858 de 1967

Berlinette Scuderia Ferrari

Châssis type 603, moteur type 237, boîte de vitesses type 603 R.

1971 - Walter Medlin, Orlando, FL, USA

1994 - restored

1994/Aug/26-28 - Monterey Historic Races, Laguna Seca Harley Cluxton

1996/Aug - offered for sale by Medlin

1998 - Medlin did not accept $9,0 Mio, asking for $11,0 Mio

2009/May/17 - NS - RM's Leggenda e Passione Maranello auction - highbid €7.25 Mio

2009 - displayed at Galleria Ferrari, Maranello, I

2012/Feb - offered by Talacrest Ltd., UK

2012/Aug - still offered by Talacrest Ltd., UK

21:40 Publié dans c.amon, l.scarfiotti, m.parkes | Tags : chris amon, l.scarfiotti, mike parkes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (3) | ![]() Facebook | |

Facebook | |

06 février 2014

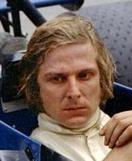

Jochen Rindt & Co: 50 ans après les débuts de Jochen en GP (face B)

... Les amis, les rivaux, les contemporains : ce qu’ils sont devenus

Remarques de Klaus Ewald, traduit de l'anglais par Francis Rainaut

A l’instar de l’allemand Bernd Rosemeyer dans les années trente et du canadien Gilles Villeneuve dans les années soixante-dix et quatre-vingt, Jochen Rindt dans la Lotus Ford 72 est considéré comme l’archétype du jeune et courageux héros de Grand Prix doté d’un charisme illimité et d’une popularité intemporelle...

19:40 Publié dans e.fittipaldi, j.brabham, j.rindt, m.andretti | Tags : b.ecclestone, j.rindt, e.fittipaldi | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | ![]() Facebook | |

Facebook | |

01 février 2014

Jochen Rindt & Co: 50 ans après les débuts de Jochen en GP (face A)

Les amis, les rivaux, les contemporains : ce qu’ils sont devenus ...

Remarques de Klaus Ewald, traduit de l'anglais par Francis Rainaut

- voir aussi le texte original en anglais Back to the roots

Quem di diligunt, adulescens moritur (Plautus, Bacchides, IV, 7, 18)

Le James Dean de la Formule Un. La première pop star jamais vue en Grand Prix. L’homme le plus rapide qui ne se soit jamais assis dans le cockpit d’une monoplace de Grand Prix, de tous les temps. Plus charismatique que Jim Clark, Jackie Stewart et Graham Hill réunis. Tué et malgré cela devenu champion du monde quelques semaines plus tard. Le premier parlant allemand. Karl Jochen Rindt (1942 – 1970) était le fils du fabriquant d’épices allemand Karl Rindt et de son épouse autrichienne Ilse Martinowitz. Né dans la ville allemande de Mainz et de citoyenneté allemande pour la vie, Rindt a perdu ses deux parents lors d’un bombardement aérien sur Hambourg en 1943 – la fabrique d’épices Klein & Rindt avait une succursale dans le fameux Speicherstadt d’Hambourg qui fait désormais partie de la nouvelle ville d’Hafen.

21:05 Publié dans a.senna, j.brabham, j.rindt, j.stewart | Tags : jochen rindt, emerson fittipaldi | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | ![]() Facebook | |

Facebook | |

26 janvier 2014

Pilotes et skieurs

Si l’on vous parle d’un long « ruban » de quelque 3,3 km qui se découpe en portions dont les noms sonnent comme une menace, tels la Mausefalle (la souricière), un impressionnant saut qui propulse les coureurs dans le vide après quelques secondes de course, et le Steilhang (la pente raide), ne pensez pas qu’il s’agit d’un quelconque remake du Nürburgring, on parle ici de la Streif, cette piste de ski alpin située à Kitzbühel en Autriche et dont la descente mythique a eu lieu le 25 janvier 2014. (1) et (2)

L’occasion rêvée de faire un parallèle (!) entre pilotes et skieurs.

Nombreux sont les « skieurs » à avoir soigné leurs trajectoires, à la fois sur les pistes verglacées et sur les pistes bitumées. Ils ont en commun les mêmes notions de vitesse, de trajectoire et de glisse. S’y ajoute un sens de l’attaque certain et une excellente maitrise technique des appuis.

Honneur aux dames, intéressons-nous en premier à la « divine » Divina Galica. La speedqueen, fille d’un presque collègue de James Bond, a participé à trois Olympiades d’hiver en slalom et en géant, à chaque fois en tant que capitaine de l'équipe féminine britannique olympique de ski et a aussi détenu un record du monde de vitesse à ski. Elle a ensuite enchaîné sur la course automobile où, après des débuts sur Formule Ford, elle a vite grimpé les marches jusqu’à la Formule 1 où, « unfortunately », elle a échoué à se qualifier aux trois Grand Prix auxquels elle était engagée, à une époque où les places sur la grille étaient très chères et son matériel pas de première jeunesse. Et je n’ai pas cité ses participations brillantes en Formule 5000, en championnat Aurora mais aussi en Formule 2 et en protos.

L’autre exemple qui nous vient immédiatement à l’esprit, est celui de Luc « Lucho » Alphand, l’enfant de Serre-Chevalier, trois fois vainqueur sur la terrible Streif et aussi triple vainqueur de la coupe du monde de descente. Luc Alphand a aussi remporté la coupe du monde de ski au général, l’équivalent d’un championnat du monde de Formule 1, une belle revanche sur ses débuts qui furent émaillés de chutes et de blessures diverses, en bref le quotidien d’un skieur de compétition. Une fois la période ski terminée, Lucho a encore remporté le Dakar 2006 et terminé 7e la même année des 24 Heures du Mans dans une Corvette de l'écurie Luc Alphand Aventures.

Ce qui m'amène en trace directe à parler de Patrick Tambay (3) et du regretté Bob Wollek, tous les deux membres de l’Equipe de France de ski, le premier en équipe Junior, le second en équipe militaire, à la glorieuse époque d’Honoré Bonnet et du roi Killy, excusez du peu.

Ce qui m'amène en trace directe à parler de Patrick Tambay (3) et du regretté Bob Wollek, tous les deux membres de l’Equipe de France de ski, le premier en équipe Junior, le second en équipe militaire, à la glorieuse époque d’Honoré Bonnet et du roi Killy, excusez du peu.

Tous les deux ont laissé une large empreinte dans le monde du ski et de la course automobile, ils ont fréquenté à la fois l'élite du ski français et la course automobile au plus haut niveau.

Puisque l’on en vient à évoquer « Toutoune », soulignons au passage sa pointe de vitesse sur quatre roues, notamment à la Targa Florio en compagnie de Bernard Cahier mais aussi au Mans avec Bob Wollek sur l’Alpine-Renault, équipage typiquement « alpin » s’il en fut.

Puisque l’on en vient à évoquer « Toutoune », soulignons au passage sa pointe de vitesse sur quatre roues, notamment à la Targa Florio en compagnie de Bernard Cahier mais aussi au Mans avec Bob Wollek sur l’Alpine-Renault, équipage typiquement « alpin » s’il en fut.

Mais Killy n'a sans doute pas souhaité s'investir « à fond » dans une deuxième carrière sportive, ayant déjà donné pas mal d'années au ski de compétition et fourmillant par ailleurs d'idées et de projets comme on a pu le constater quelque temps après.

Avant eux il y eut l’avalin Henri Oreiller, le « fou descendant » vainqueur de la descente des J.O. en 1948, qui se consacra plus tard à la course automobile avec un brio certain, fut sacré Champion de France Tourisme des Rallyes en 1959, avant de se tuer en 1962 à Montlhéry à l’âge de 37 ans au volant de sa Ferrari 250 GTO , lancé à la poursuite du suisse Edgard Berney également sur Ferrari 250 GTO.

Henri fut par ailleurs engagé volontaire dans la SES (Section d’Eclaireurs Skieurs), une unité de la Résistance.

Citons ensuite pêle-mêle le géantiste Georges Coquillard, le bobsleigheur britannique Robin Widdows (4), et chez les dames la grande "Christine" Beckers.

Citons ensuite pêle-mêle le géantiste Georges Coquillard, le bobsleigheur britannique Robin Widdows (4), et chez les dames la grande "Christine" Beckers.

Plus prêt de nous n'oublions pas le free rider Guerlain Chicherit (5) aussi à l’aise à ski que dans les montagnes d’Amérique du Sud.

Enfin chez les pistards, nous mentionnerons Jacques Laffite dont le talent, dit la légende, fut détecté skis aux pieds, le grenoblois Johnny Servoz-Gavin ex-moniteur dixit sa bio, François Cevert et Jochen Rindt skieurs assidus, et bien sûr Sébastien Ogier lequel est au passage moniteur de ski.

Pour terminer il serait dommage ne pas citer Fernand Grosjean, le grand-père de Romain, qui fut vice-champion du monde de ski - pour la Suisse, nul n’est parfait - en 1950.

Il n’est donc pas surprenant que Michael Schumacher apprécie autant le ski, nous lui dédions tout naturellement cet article, écrit par un skieur pratiquant régulièrement depuis près de cinquante ans.

Francis Rainaut

(1) http://www.hahnenkamm.com/programm-2014.html

A suivre sur Eurosport

(2) «A Kitzbühel, on a un petit peu peur, et parfois très peur. Il n'y a pas beaucoup de descentes qui vous font cet effet», souligne le Norvégien Aksel Lund Svindal. «Elle est horrible, vous partez et les premières trente secondes sont un mélange entre tenter d'aller vite et tenter de survivre, c'est pourquoi l'atmosphère est si différente ici», estime le double vainqueur de la Coupe du monde 2007 et 2009.

(3) Champion de France junior de descente en 1968, sélectionné en équipe nationale B

(4) Finaliste aux J.O d’Innsbruck 1964

(5) Quadruple champion du monde de ski freeride

Illustrations :

- Divina Galica J.O. © DR

- Divina Galica Chevron F2 © DR

- Bob Wollek © DR

- Patrick Tambay, Val d’Isère © DR

- Jean-Claude Killy, Nürburgring 1968 © DR

- Henri Oreiller, St-Moritz 1948 © DR

- Robin Widdows, Cooper-BRM © DR

- Jochen Rindt © DR

- Bernie & Niki 2014 © DR

18:00 Publié dans d.galica, p.tambay | Tags : divina galica, patrick tambay, jc killy | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | ![]() Facebook | |

Facebook | |

02 novembre 2012

The Chequered Flag

« Bonjour,

Quelles surprises de découvrir ce nouveau mds, lectrice assidue et muette de l'ancien, on ne peut que féliciter celui ou ceux qui essaient de faire vivre un état d'esprit.

La première surprise, la bonne, est donc la découverte de ce site...

... Puisse ce nouveau site nous faire vibrer encore longtemps, et regrouper les anciens contributeurs sans esprit partisan autre que celui d'entretenir la mémoire collective, qui par définition ne peut appartenir à un seul individu, fût-il ex TTDCB.

Bien cordialement.»

JS

Merci à JaC, alias Raymond Jacques, pour la qualité de ses textes et de ses illustrations.

Merci à François Blaise pour ses émouvantes photos.

Merci à Gérard Gamand,

Merci à Michael,

Merci à Bruno,

Merci à Lucien Van Danléwoëlle,

(Merci à Pierre Ménard),

(Merci à patrice vatan),

Merci à Olivier ROGAR,

Merci à philippe7,

Merci à louis P.Julien,

Merci à Daniel DUPASQUIER,

Merci à Marc Gualtiéri,

Merci à Jacques Privat,

Merci à ferdinand,

Merci à JaC,

Merci à François Blaise,

Merci à Dominique LHOMME,

Merci à Viceroy,

(Merci à passion91),

Merci à Jean PAPON,

Merci à JYMasselot,

Merci à laurent riviere,

Merci à Frédéric CHARLES,

Merci à jean-claude derringer,

Merci à GHua,

Merci à laurent T,

Merci à René Fiévet,

Merci à JS,

Merci à jean-paul orjebin,

Merci à François Libert,

Merci à JP Squadra,

Merci à Linas27,

Merci à de passage,

Merci à Christian Burdet,

Merci à Bernard Schoonjans,

Merci à GERIC,

Merci à Emmanuel,

Merci aux 5770 visiteurs de ce blog

Francis Rainaut, 2 novembre 2012.

En post scriptum, spécialement pour Gilles Hua, voici l'autographe que Piers m'a signé en 1969

17:10 Publié dans p.courage | Tags : piers courage | Lien permanent | Commentaires (16) | ![]() Facebook | |

Facebook | |